THE CARROLL HOUSE

Towering Over Spa Creek

For more than three centuries the Charles Carroll House has stood as a prominent example of Annapolis' cultural and aesthetic vibrancy. The house itself, begun about 1690), is now managed by the Charles Carroll House of Annapolis, Inc. for the Redemptorists of Maryland. Archaeological excavations were conducted onsite for four seasons, beginning in 1986. This work focused on documenting the lives of Carroll House inhabitants and shed light on the differing worldviews of the mansion's 18th and 19th-century inhabitants. Among those glimpsed archaeologically are members of the Carroll family, including Charles Carroll of Carrollton, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and people of African and African American descent who worked the property as slaves. The Carroll family owned more than 1,000 slaves during their time on this property.

What is Left from Africa?

Unsatisfied with being told only about slavery and the destruction of African cultures in the Middle Passage, Black Annapolitans posed a series of profound questions, including: What was left from Africa? What happened to African culture once our ancestors came to the New World? Where can we see remnants of these cultures today? Archaeological excavations conducted on the ground floor of the Carroll House provided several leads in answering these questions. Later, it became known that these rooms were the living quarters of enslaved Africans and African Americans throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. The east wing/ground floor of the Carroll House became a focus for archaeological excavations in 1991. The materials recovered from this area served to both confuse and inspire archaeologists for several years.

A Remarkable Discovery

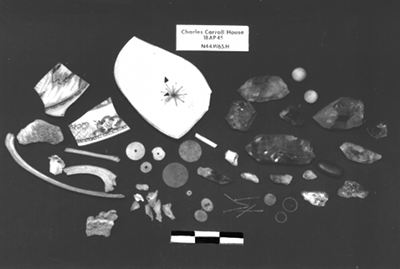

In a series of workrooms with clear 18th and 19th century occupations, a number of artifacts dating between 1790-1820 were encountered by a volunteer excavator along with 12 quartz crystals. The quartz crystals were found in one room's northeast corner. A pearlware bowl manufactured in England with a blue asterisk decoration on its base was found placed face-down, covering the crystals, pieces of chipped quartz, a faceted glass bead, and a polished black stone. But what did these artifacts mean? And why would they have been placed deliberately underneath the bowl in the room's northeast corner?

At the time of discovery, the meaning and significance of these materials were unknown. We knew that the artifacts had been intentionally deposited in the room, and that they had most likely been associated with the African and African American slaves who worked at the Carroll House. Having never encountered similar materials in a context such as this, we were particularly grateful when Dr. Frederick Lamp (Curator of African Art at the Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD) telephoned to suggest that the materials be interpreted as an Nkisi. We soon learned that Nkisi are Central West African religious artifacts that are used in divination rituals by BaKongo peoples in West Africa. No one in Annapolis had ever found anything tied so clearly to African culture.

Interpreting African Survivals

The fact that people of African descent deposited religious artifacts clearly displaying elements of Bakongo origin in the ground at the Carroll House lends credence to the idea that New World slaves retained traditional cultural practices well into the 19th century. This refutation of the commonly held idea that those of African descent had been stripped completely of their heritage is an important discovery and suggests that African culture survived in slavery and, equally important, that the history of Annapolis includes African culture. Thus, while it is impossible to fully understand the lives of those who lived hundreds of years ago, we do now know something of what is left from Africa.

Ostentatious Landscapes

At roughly the same time that enslaved Africans and African Americans were living in the east wing of the mansion, Charles Carroll of Carrollton was actively engaged in the practice of his own traditions. One of the most noticeable aspects of the house today is a largely intact 18th-century formal garden that survives. Constructed around 1770, the Carroll garden stood out as a perfect environment in which to explore how the Carroll family presented themselves publicly by controlling multiple views of their property on the eve of the American Revolution. Four seasons of archaeological investigation focused on finding the original 18th-century garden and committing its spatial relationships to paper so that they might be more clearly understood.

Mathematics of an 18th Century Garden

When first viewed, the Carroll garden presents itself in a rather odd configuration. Shaped in the form of a triangle that is constructed from a series of five terraces complete with turf ramps, the garden is bordered on its street side by a head-high wall and on its waterfront side by what in the 18th century had been a 400 ft-long sea wall. When surveyed by archaeologists and mapped out on paper, the garden was interpreted as a near perfect 3-4-5 right triangle, utilizing the base measure of the original section of the Carroll House as a basic unit of measurement whose dimensions would be played out across the garden. Seen as common in 18th century garden design, the garden's creators clearly displayed knowledge of geometry and sought to invoke ideals of the "Golden Ratio" derived from Enlightenment principles of harmony with nature. But why the construction of a garden in the shape of a near perfect right triangle?

Controlling Visions

The original construction of the Carroll garden appears to have been based on ideas of controlling sight, both by restricting sight into the garden from the outside by use of the garden wall, as well as directing lines of sight within the garden itself. One of the Carroll garden's most interesting elements is the intentional creation of optical illusions based on the increasing width of the garden's five terraces as one approaches the water. Seen from the water, the optical illusion has the effect of making the Carroll mansion seem larger and taller than it actually is. The combination of decreasing widths of the terraces and the aid of a retaining wall, thus obstructing the view of the house's inauspicious ground floor, has the effect of obscuring the actual distance to the house. Conversely, seen from inside the garden, the foreshortening effects of the terraces and the framing of the scene by two octagonal pavilions set at either end of the sea wall, bring the view of the distant shore much closer. This effectively opens up the view between the house and the far shore of Spa Creek as in many period landscape paintings.

Vision and Power

Four field seasons of archaeological investigations at the Carroll House culminated in interpretations of two separate worldviews within a single household, one African and the other European. In both instances, people made active use and manipulation of their surroundings to effect positive changes in their daily lives. Archaeology proves an effective tool for providing tangible proofs of such strategies.

Further Reading

Jones, Lynn Diekman

1995 "The Material Culture of Slavery from an Annapolis Household. Paper presented at the 1995

meetings of the Society for Historical Archaeology, Washington D.C." on file: Historic Annapolis

Foundation, Annapolis

Kryder-Reid, Elizabeth

1994 As is the Gardener, so is the Garden: The Archaeology of Landscape as Myth. In Historical

Archaeology of the Chesapeake, edited by Paul A. Shackel and Barbara J. Little, pp.131-148.

Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington DC

1996 The Construction of Sanctity: Landscape and Ritual in a Religious Community. In Landscape Archaeology: Reading and Interpreting the American Historical Landscape, edited by Rebecca Yamin and Karen Bescherer Metheny, pp.228-248. The University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville.

Leone, Mark P. and Gladys-Marie Fry

1999 Conjuring in the Big House Kitchen: An Interpretation of African American Belief Systems Based

on the Uses of Archaeology and Folklore Sources. Journal of American Folklore 112(445):372-403.

Leone, Mark P. and Paul A. Shackel

1990 Plain and Solid Geometry in Colonial Gardens in Annapolis, Maryland. In Earth Patterns: Essays

in Landscape Archaeology, edited by William M. Kelso and Rachel Most, pp.153-167. University Press

of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Logan, George C., Thomas W. Bodor, Lynn D. Jones, Marian Creveling

1992 "1991 Archaeological Excavations at the Charles Carroll House in Annapolis, Maryland, 18AP45,"

on file: Maryland Historical Trust: Crownsville, MD; and Historic Annapolis Foundation, Annapolis.